Beijing: Coco Wen recently purchased a new iPhone at a significantly reduced price, taking advantage of China’s latest consumer subsidies. However, like many others, she has cut back on other expenses.

“I usually celebrate my birthdays with a fancy meal, but this year I skipped that,” said the 31-year-old, who works for a tourism agency that has reduced her salary due to a decline in overseas travel demand.

“Our family’s spending habits have changed to only buying what’s necessary,” Wen added, noting that she now prefers cooking at home instead of dining out.

Short-Term Gains, Long-Term Trade-Offs

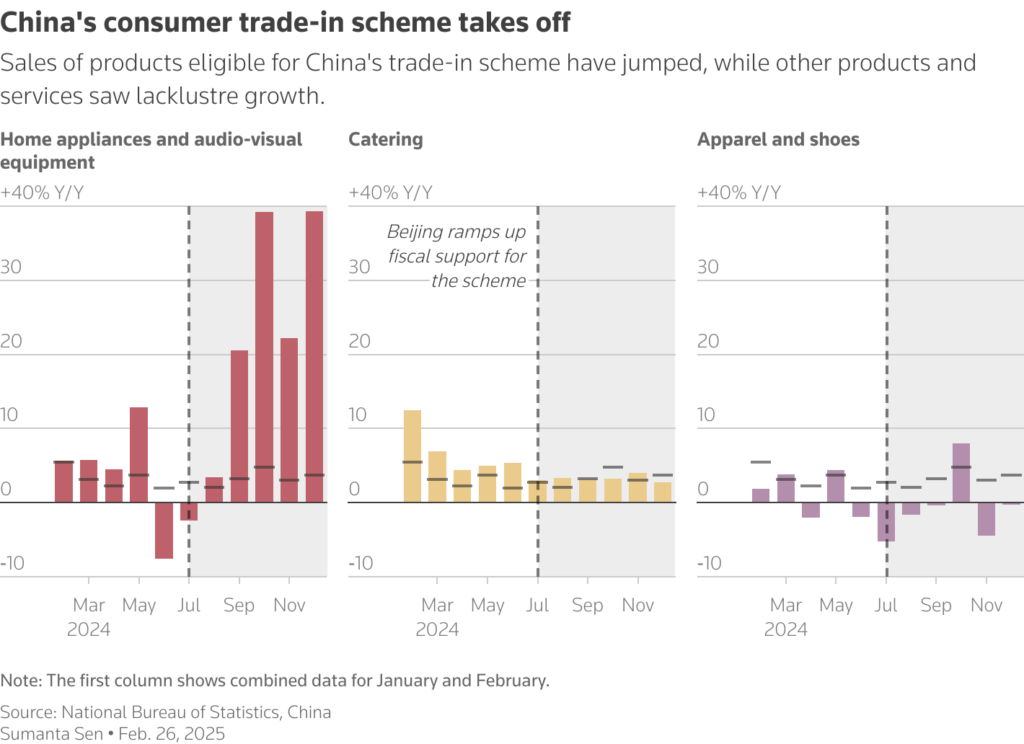

China’s latest effort to stimulate consumption—its trade-in program for electric vehicles, appliances, and consumer electronics—provides short-term economic relief but carries long-term trade-offs. While the subsidies encourage immediate spending, they also lead households to reduce purchases of unsubsidized goods and services. Additionally, the program risks suppressing future demand, as consumers may not replace their cars and appliances for years.

“It could be harmful from the perspective of a five-to-six-year cycle,” said Xing Zhaopeng, senior China strategist at ANZ.

This has intensified calls for policymakers to introduce more comprehensive, long-term measures to strengthen household spending. With the National People’s Congress (NPC) set to begin its annual session on March 5, expectations are high for new consumer-focused initiatives.

Domestic Consumption as a Growth Driver

China increasingly relies on domestic consumption to counteract the impact of its trade war with Washington. As global demand weakens and tariffs rise, Beijing needs Chinese consumers to compensate for declining foreign purchases of Chinese goods.

Although China achieved its 5% economic growth target last year, economists caution that excessive reliance on exports has created industrial overcapacity and deflationary pressures.

“China has a serious overcapacity problem,” said Louis Kuijs, chief Asia economist at S&P Global. “Domestically, this is weighing on prices and profits. Externally, it is amplifying a pushback against Chinese exports. Raising consumption would really help.”

Kuijs emphasized the need for government initiatives in health, education, and social security to encourage spending confidence, adding that he was “keen to see any plans the government has on raising its role and spending” in these areas.

Scale of Reform Matters

While Beijing has pledged to “vigorously” boost consumption, including by raising incomes, pensions, and medical subsidies, the scale of past initiatives has been modest.

Last year, China increased the minimum pension by 20 yuan ($2.76) to 123 yuan per month, benefiting 170 million people. However, this effort amounted to less than 0.01% of the country’s $18.6 trillion GDP.

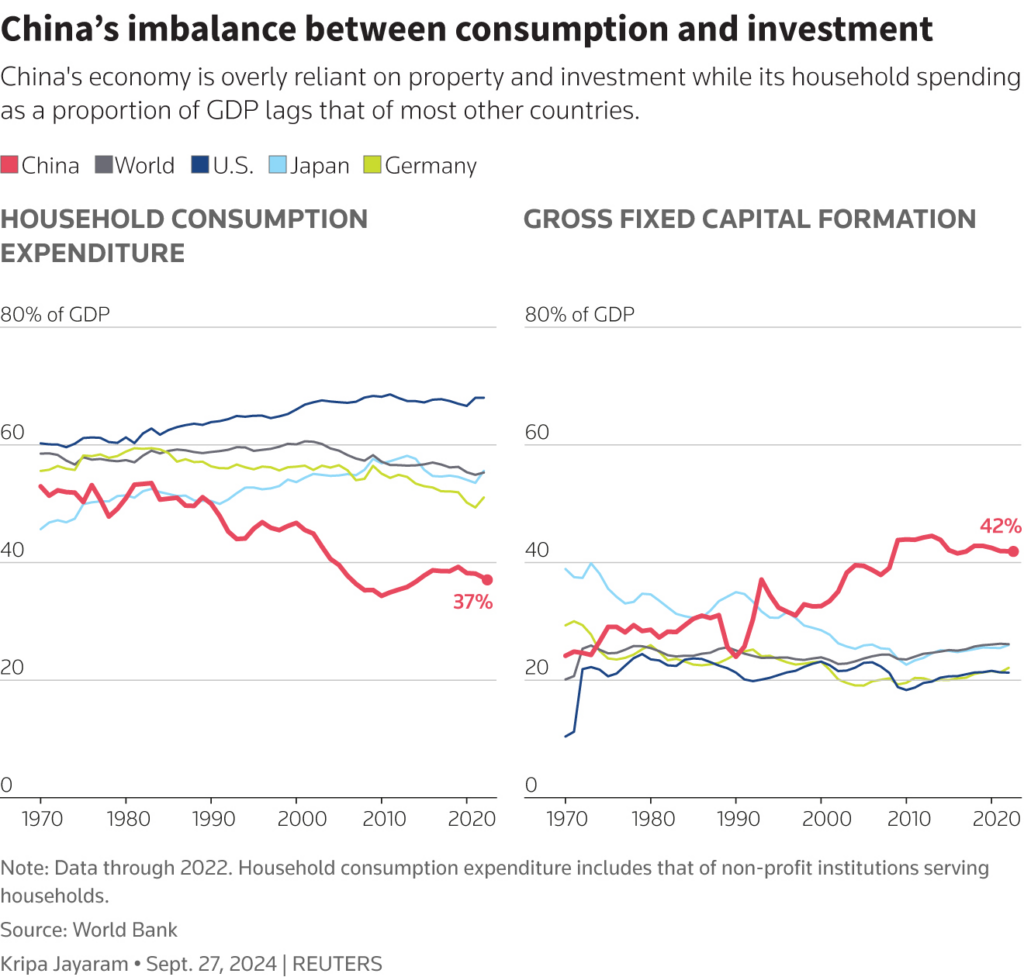

With household spending accounting for less than 40% of China’s GDP—about 20 percentage points below the global average—closing this gap requires significant policy changes.

Analysts argue that reforms should focus on redistributing resources from businesses and government sectors to consumers. This would involve tax system adjustments, a stronger social safety net with higher pensions and unemployment benefits, and further dismantling of China’s internal passport system to reduce rural-urban inequality.

However, such measures could shift resources away from export-driven industries and slow down President Xi Jinping’s push for “new productive forces” in technology and manufacturing.

“While Beijing has acknowledged the urgency of boosting domestic consumption, its policy response so far has fallen far short of the structural reforms needed to shift China’s economic model in a meaningful way,” said Camille Boullenois, associate director at Rhodium Group.

Also Read | Canada’s Privacy Watchdog Investigates X Over AI Data Use

Rhodium estimates that the structural policy changes required to boost consumption could cost around 30% of China’s GDP.

“Beijing has reform options available, though they vary in financial and political viability,” Boullenois added.

Debt-Driven Growth?

Premier Li Qiang is expected to announce a 2025 growth target of around 5% in his upcoming NPC address. However, economists caution that sustaining high growth without transitioning to new economic drivers will likely require more debt, especially amid trade tensions and the property sector crisis.

Xu Hongcai, deputy director of the economic policy commission at the state-backed China Association of Policy Science, tempered expectations for sweeping reforms, stating, “We should not have high hopes on big reforms.”

Also Read | Robotic Caregivers: The Future of Elderly Care in Japan?

Instead, Li is expected to announce a widened budget deficit and record special debt issuance plans.

“We must ensure external shocks don’t impact our economic growth,” said one policy adviser on condition of anonymity. “Boosting consumption is key, alongside efforts to boost investment and trade.”