London: In a significant archaeological breakthrough, researchers have uncovered rare forensic evidence of a gladiator’s deadly encounter with a lion in ancient Roman Britain. The discovery centers on a skeleton found near York—known during Roman times as Eboracum—that bears unmistakable bite marks from a large feline, likely a lion, suggesting the man met his end in the arena.

The remains belong to a man believed to be between 26 and 35 years old at the time of his death in the 3rd century AD. Eboracum, then a crucial military outpost in Roman Britannia, now emerges as a site of gladiatorial combat once thought to be limited to Rome and other major imperial cities.

“Forensic analysis reveals puncture and scalloping on the pelvis, indicative of large dentition piercing soft tissue and bone,” said Tim Thompson, a forensic anthropologist at Maynooth University in Ireland and lead author of the study published in PLOS ONE.

“We don’t think that this was the killing wound, as it would be possible to survive this injury, and it is in an unusual location for such a large cat. We think it indicates the dragging of an incapacitated individual.”

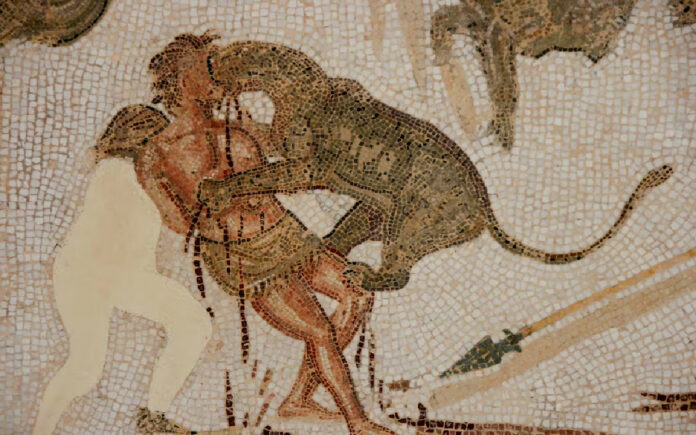

This remarkable evidence is the first direct physical proof of a human-animal fight from the Roman world, according to the research team. While Roman mosaics and texts have long portrayed these brutal spectacles, definitive skeletal evidence has remained elusive—until now.

A Glimpse Into Roman Arena Culture

The Romans showcased a wide range of wild animals in their arena events, including lions, tigers, leopards, bears, bulls, ostriches, elephants, rhinos, and crocodiles. These creatures were often matched against venatores, gladiators specialized in animal combat.

“Predatory animals—above all big cats but also sometimes other animals, for example bears—were pitted as combatants against specialist gladiators, known as venatores,” said co-author John Pearce, a Roman archaeologist at King’s College London.

In some cases, animals were used not for sport but for executions, known as damnatio ad bestias, where condemned individuals were thrown to starved beasts, often while bound and defenseless.

Also Read | Pinelands Blaze in New Jersey May Become State’s Biggest Wildfire Since 2007

Pearce painted a grim picture of the York gladiator’s final moments:

“Very speculatively, from the gladiator’s perspective, perhaps an approach like a matador’s would have been applied—to dodge and progressively wound, so as to extend the performance.

In this case, clearly that ended unsuccessfully, with it being likely, given the position of the bite mark, that the lion is mauling or dragging this individual on the ground.”

A Violent End—and an Unusual Burial

The remains reveal more than just evidence of the final encounter. The man had suffered spinal abnormalities, likely from repetitive strain or overloading—hallmarks of the gladiator lifestyle. Dental disease was also present. His decapitation, likely a final blow after defeat, suggests a violent death in the arena.

Also Read | Trump and Zelensky Lock Horns Again as U.S. Threatens to Walk Away from Peace Talks

He was buried with two other men, and strikingly, horse bones were found overlaying the bodies—an unusual ritual whose meaning remains unclear. The burial ground near York has yielded 82 skeletons to date, mostly of physically robust young men, many showing signs of severe injury and decapitation, pointing to gladiatorial combat.

Although no amphitheater has yet been located in Eboracum, remnants of the Roman city’s walls and buildings still stand, offering tantalizing clues about life—and death—in one of the empire’s distant outposts.

Also Read | EU Slaps Fines on Apple and Meta for Violating Digital Markets Act

“This is a reminder of the spectacle culture central to Roman public life,” Pearce said.

“This new analysis gives us very concrete and specific evidence of a human-animal violent encounter, either as combat or punishment, showing that the big cats caught in North Africa were shown and fought not only in Rome or Italy but also surprisingly widely, even if we don’t know how frequently.”