Kingston/London: A growing number of Jamaicans are calling for the country to sever its remaining colonial ties as the government moves forward with a bill to remove King Charles as head of state. While many support the proposal, some critics argue that the reforms should go further to ensure true independence.

Jamaica gained independence from Britain in 1962 but, like 13 other former British colonies, still retains the British monarch as its head of state. Public sentiment has shifted significantly in recent years, leading Prime Minister Andrew Holness’s government to introduce a bill in December aimed at removing King Charles. However, some believe the legislation does not go far enough in breaking away from Jamaica’s colonial past.

Colonial Legacy and Calls for Reparations

The push to remove the British monarch comes amid growing demands from African and Caribbean nations for reparations to address the lingering effects of slavery and colonialism. Hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were brought to Jamaica during the transatlantic slave trade, and advocates argue that the legacy of colonial rule has contributed to enduring inequalities.

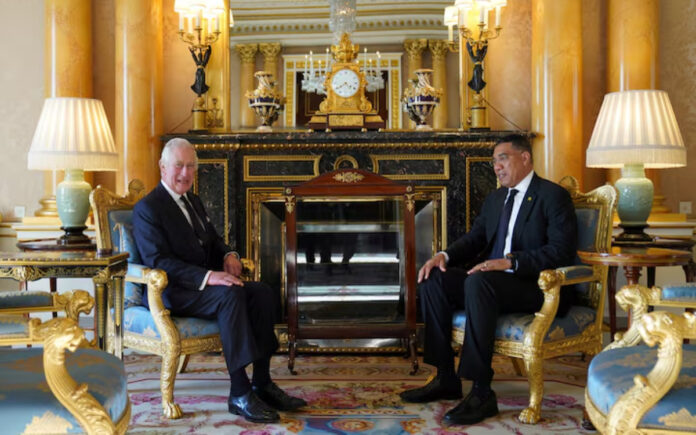

While Britain has rejected calls for reparations, Buckingham Palace has maintained that decisions on the monarchy’s role should be left to the people and their governments. During a 2022 visit to the Bahamas, Prince William—now heir to the throne—stated that he supports and respects any decision Caribbean nations make regarding their future governance.

The proposed bill, which could be debated in parliament as soon as this month or next, must be ratified by a national referendum if passed. However, opposition figures and other critics have raised concerns about the selection process for a future head of state and the continued role of the British Privy Council as Jamaica’s final court of appeal.

Debate Over Jamaica’s Future Presidency

The government’s bill proposes replacing the governor-general—King Charles’s representative in Jamaica—with a president. Under the current plan, the prime minister would nominate a candidate in consultation with the opposition leader. If no consensus is reached, the opposition leader could suggest a nominee, and if that is also rejected, the prime minister would have the final say, with parliament voting on the choice.

Some critics, including members of the opposition People’s National Party (PNP), argue that this selection process grants too much power to the prime minister. Donna Scott-Mottley, the PNP’s justice spokesperson, warned that the bill could enable a sitting leader to install a political ally as president.

“If you (PM) wanted your right-hand man to become president, you simply do the nomination,” Scott-Mottley told Reuters.

Former Prime Minister P. J. Patterson echoed these concerns, arguing that the proposed president would merely be “a puppet of the prime minister.” The government has not responded to these criticisms.

Jamaica’s move to remove the British monarch has gained momentum following Barbados’s decision to become a republic in 2021. During a 2022 visit from Prince William, Prime Minister Holness made it clear that Jamaica sought to be “independent.” A 2022 poll by Don Anderson found that 56% of Jamaicans supported removing the monarchy, a significant increase from 40% a decade earlier.

Push for ‘Full Decolonisation’

While the governing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) has the two-thirds majority needed to pass the bill in the lower house of parliament, it will require at least one opposition vote in the upper house. If the bill fails there, the government can still put it to a national referendum, which it aims to hold by next year. The referendum would need at least two-thirds of the vote to pass. However, the process could be delayed by Jamaica’s upcoming general election.

Another contentious issue is the continued role of the London-based Privy Council as Jamaica’s final court of appeal. Critics argue that Jamaica should instead adopt the Trinidad-based Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), as other Caribbean nations like Barbados, Belize, and Guyana have done.

Accessing the Privy Council is costly and bureaucratic, requiring a visa to travel to the UK. Some critics believe that retaining it contradicts the goal of cutting colonial ties. The government has stated that judicial reforms will come later as part of a phased approach, with Jamaicans having the opportunity to weigh in on the matter.

Also Read | UK Grants £2.26 Billion Loan to Ukraine as Starmer Reaffirms Support for Zelenskyy

Christopher Charles, a professor at the University of the West Indies, compared keeping the Privy Council to wanting a divorce while still maintaining “a room in the matrimonial home.”

Scott-Mottley called it “anachronistic” to remove the British monarch while still relying on a British court.

Haile Mika’el Cujo, a constitutional change advocate, warned that keeping the Privy Council might discourage voters from supporting the referendum.

Also Read | Ukrainian Soldiers Weigh In on Trump-Zelenskyy Clash, Stress Need for Support

“People are not going to sign off on that,” Cujo said.

Disagreements over the Privy Council have already led the PNP to pause its involvement in the committee working on the bill.

PNP leader Mark Golding reinforced his party’s stance, stating, “We believe that time has come for full decolonisation… not piecemeal or partial or phased.”