This year’s exceptionally warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico contributed to Hurricane Milton’s swift transformation, earning it the title of the third-fastest intensifying Atlantic storm on record, according to the U.S. National Hurricane Center. Scientists are pointing to Milton’s rapid power surge as the latest example of a troubling trend: climate change is not only fueling stronger storms but making them intensify faster.

What Drives a Hurricane’s Power?

Hurricanes gather energy from heat in surface waters as their winds organize. The warmer the water, the more fuel a hurricane has to strengthen. Due to climate change, water temperatures are steadily rising. Over the past four decades, oceans have absorbed about 90% of the excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions.

This year, 2024, has seen exceptionally warm waters, and the world is on track to set a record for the highest average global air temperature. The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported that the past 12 months saw global temperatures rise 1.62°C (2.92°F) above pre-industrial levels.

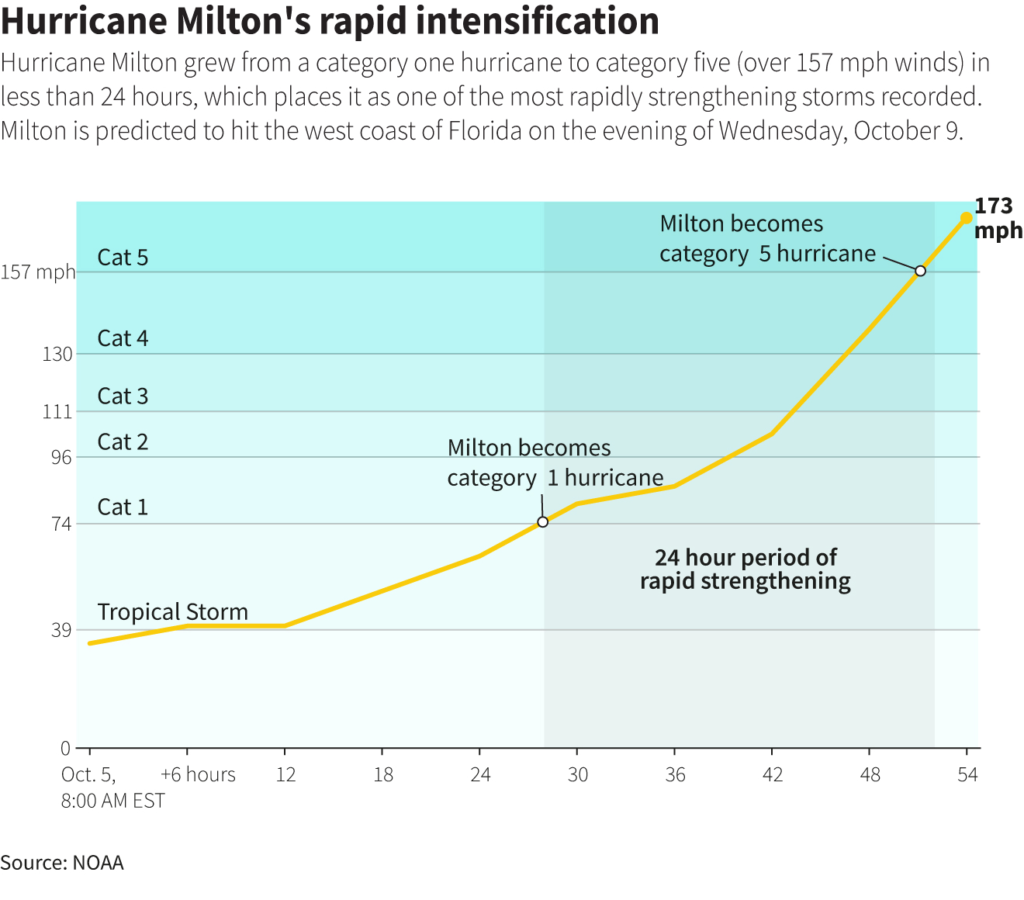

A hurricane’s strength is measured by its sustained wind speeds. A Category 1 hurricane has wind speeds of 74-95 mph (119-153 kph), while a Category 5 hurricane reaches speeds of 157 mph (252 kph) or higher.

What’s the Difference Between Storm Strength and Rapid Intensification?

When a storm intensifies quickly, scientists refer to it as “rapid intensification.” This occurs when sustained wind speeds increase by at least 35 mph (56 kph) within 24 hours, allowing a storm to jump up two categories.

Milton exemplified this phenomenon on Monday when its wind speeds far exceeded the rapid intensification threshold. In less than a day, it transformed from a tropical storm to a powerful Category 5 hurricane.

“The warm Gulf waters and conducive air conditions made Milton’s rapid intensification a near-certainty,” said Gregory Foltz, a physical oceanographer at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

A 2023 study in Scientific Reports revealed that Atlantic storms are now more than twice as likely to intensify from Category 1 to Category 3 within 36 hours compared to past decades. The study estimated a 29% overall increase in rapid intensification for Atlantic storms, though this effect might be less pronounced for Gulf storms. Despite this, unusually warm waters can still fuel rapid intensification in the Gulf, Foltz noted.

NOAA data showed that the Gulf of Mexico surface waters reached record temperatures around 90°F (32°C) during the past two summers. In mid-September, just weeks before Milton formed, the Gulf experienced its warmest temperatures on record for that time of year.

“Watching Milton’s strengthening unfold in real time yesterday was still staggering,” said Andra Garner, a climate scientist at Rowan University. Her calculations, shared with Reuters, placed Milton’s intensification rates in the 99th percentile of all observed maximum rates in the Atlantic.

Also Read | Surprise Cancellation: Israel’s Defense Minister Calls Off U.S. Visit

Why Is Rapid Intensification So Dangerous?

Hurricanes pose a serious threat to life and property, often resulting in some of the costliest disasters. In fact, the 10 most expensive U.S. disasters have all occurred since 1989. While Milton’s rapid intensification was alarming, it happened while the storm was still days away from landfall, giving Florida communities enough time to evacuate.

However, when rapid intensification happens near the shore, it can catch communities off guard, leaving little time for preparation or evacuation. Last year, Mexico experienced this when a weak tropical storm in the Pacific suddenly strengthened into a Category 5 storm—Hurricane Otis—before slamming into the Acapulco area, killing dozens.

The most rapidly intensifying Atlantic hurricane on record remains Hurricane Wilma, which became a Category 5 storm when it struck the Yucatán Peninsula in 2005, followed by Hurricane Felix in 2007.

A 2022 study published in Geophysical Research Letters found that the intensification rates of near-shore Atlantic hurricanes significantly increased between 1979 and 2018. However, similar to the 2023 study, it did not identify a major change in intensification speeds for Gulf storms.